Arithmetic and Control Unit Design

Floating point

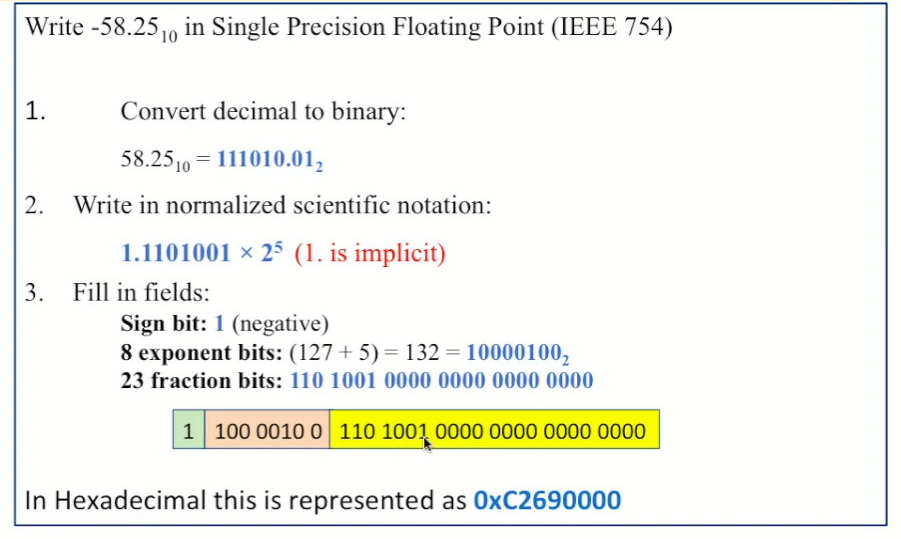

Example

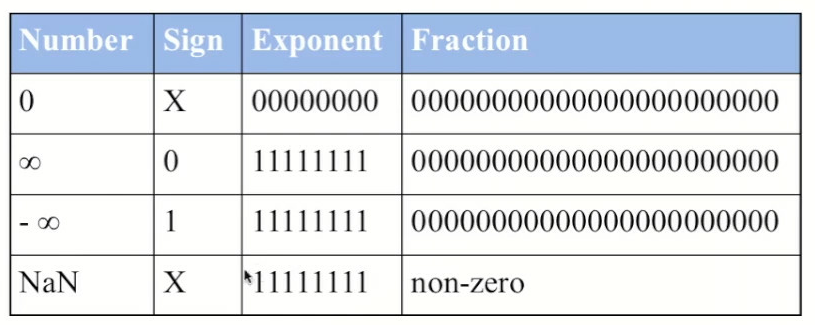

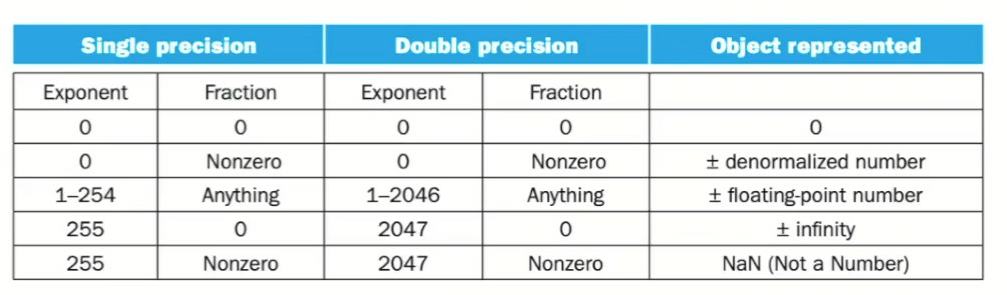

Special Cases

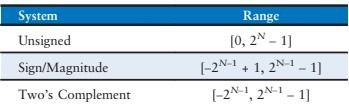

Range

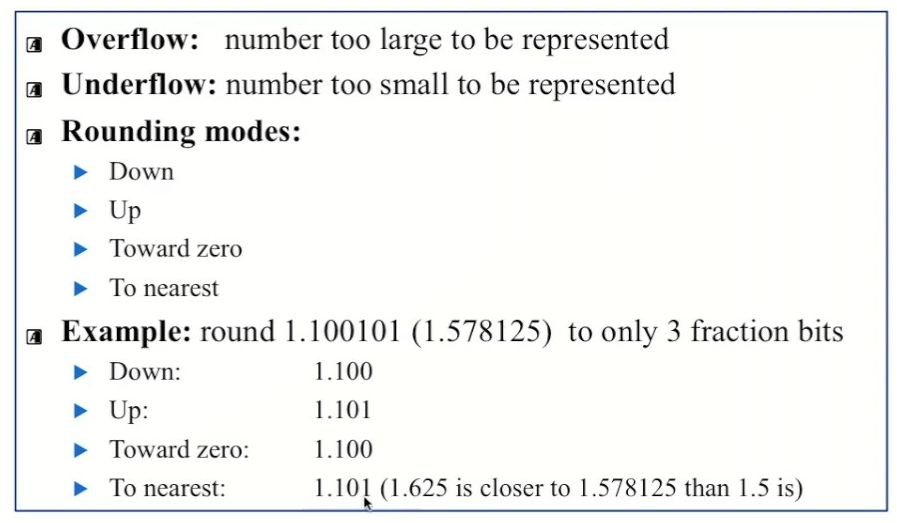

Rounding Modes

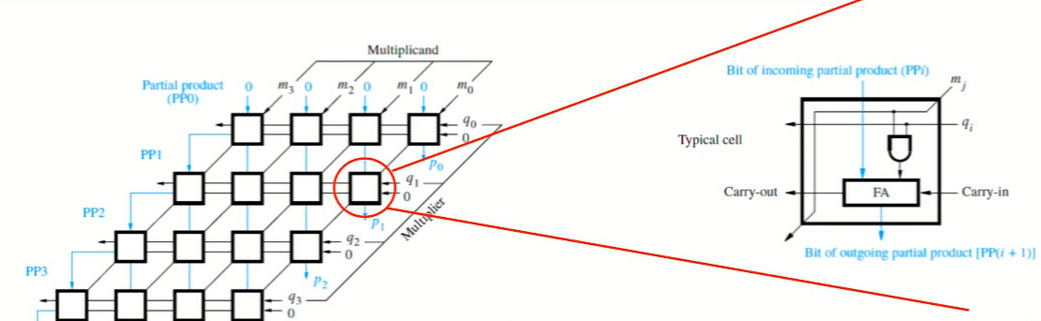

Array Multiplication

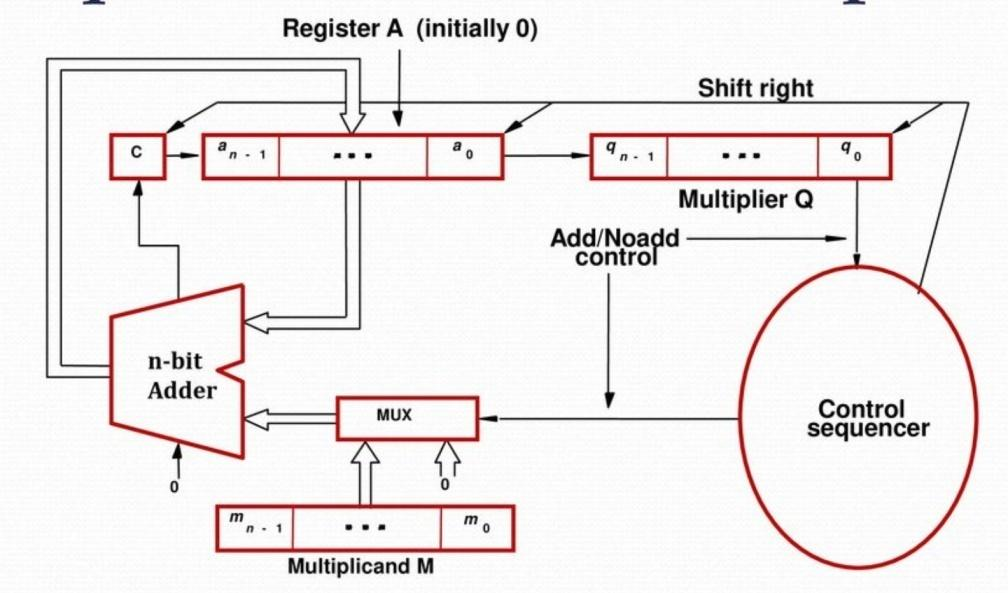

Implementation

- Use an Adder circuitry to do repeated addition

- Multiplication through spatial addition, requires a single n-bit adder doing addition n times.

- After every addition, the result has to be shifted right once.

- Monitor the multiplier bit to add multiplicand to the partial product.

- Repeat the add – shift right process for the number of multiplier bits.

- All the control signals has to be generated for this sequential process appropriately, by a control sequencer.

- Requires n-cycles for n times addition.

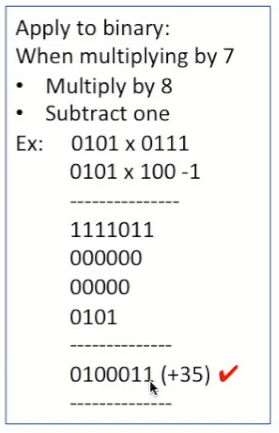

Booth Multiplication

Booth recoding is a technique that makes multiplication more efficient by replacing strings of 1s with 0s and recoding the multiplier to a set of digits

Hardwired vs. Microprogrammed Control: A Comparison

The two primary methods for implementing control units in processors: hardwired control and microprogrammed control. Each approach has its own advantages and disadvantages, creating tradeoffs in design considerations.

Hardwired Control

- Implementation: Involves a direct, physical connection of logic circuits to generate control signals. These circuits, consisting of logic gates like AND, OR, and XOR, are specifically designed to produce the correct sequence of control signals for each instruction in the processor’s instruction set.

- Speed: Offers faster execution because the control signals are generated directly by the hardware. This direct implementation leads to a shorter delay in generating control signals, making it suitable for applications where speed is critical.

- Complexity and Flexibility: Can become very complex for processors with large and sophisticated instruction sets. Modifying or adding instructions later in the design process can be challenging due to the fixed nature of the hardware implementation.

Microprogrammed Control

- Implementation: Employs a program-like approach where control signals are stored as microinstructions in a dedicated control store (a special memory). Each microinstruction corresponds to a specific control signal or a set of control signals.

- Flexibility: Provides greater flexibility in design and implementation. Modifying or adding instructions is simpler as it involves changing the microprogram in the control store, not the hardware. This adaptability is particularly beneficial for complex instruction sets, such as those found in CISC (Complex Instruction Set Computing) architectures.

- Speed: Generally slower than hardwired control due to the time required to fetch microinstructions from the control store and decode them.

Summary of Tradeoffs

- Speed vs. Flexibility: Hardwired control offers speed but lacks flexibility, while microprogrammed control provides flexibility at the expense of some speed.

- Complexity vs. Simplicity: For simple instruction sets, hardwired control can be simpler to implement. However, as instruction sets grow more complex, microprogrammed control becomes more manageable due to its programmable nature.

Choosing Between Hardwired and Microprogrammed Control

The choice between the two approaches depends on various factors:

- Instruction Set Complexity: For processors with simple instruction sets and a focus on speed, hardwired control might be preferable. Complex instruction sets benefit from the flexibility of microprogrammed control.

- Design Flexibility: If the processor design needs to be adaptable to future modifications or extensions, microprogrammed control is advantageous.

- Performance Requirements: Hardwired control is suitable when achieving maximum performance is paramount. Microprogrammed control might be acceptable if some performance tradeoff is tolerable for the sake of flexibility.

Multiplication Method Comparison: Array vs. Shift-Add

The sources describe two main methods of multiplication: array multiplication and shift-add multiplication. Let’s examine the hardware costs and speeds of each:

Array Multiplication

- Hardware Costs: Array multiplication is described as “very hardware intensive” and “expensive & waste of resources”. It utilizes an array of combinational elements, with each cell containing an AND gate and a full adder. This means the number of gates required increases significantly with the size of the numbers being multiplied.

- Speed: Array multiplication is faster than shift-add because it performs all the partial product calculations in parallel. However, the addition of the partial products still requires some time, and the overall speed is limited by the propagation delay through the array.

Shift-Add Multiplication

- Hardware Costs: Shift-add multiplication is less hardware intensive than array multiplication. It uses a single n-bit adder and a few registers to perform the multiplication sequentially. This method reduces hardware costs significantly, especially for larger numbers.

- Speed: Shift-add multiplication is slower than array multiplication because the addition of partial products happens sequentially. It requires n cycles for n-bit numbers, as it iterates through each bit of the multiplier.

Summary

Here’s a table summarizing the comparison:

| Method | Hardware Costs | Speed |

|---|---|---|

| Array Multiplication | High | Faster |

| Shift-Add | Lower | Slower |

Conclusion: The choice between array and shift-add multiplication depends on the specific application requirements. If speed is a priority, array multiplication is preferred, but at a higher hardware cost. If cost is a primary concern, shift-add multiplication offers a more economical solution, albeit with a trade-off in speed.

Computer Arithmetic Algorithms: Functions and Differences

The sources describe two main categories of multiplication algorithms and two main categories of division algorithms:

Multiplication

- Array Multiplication: This method uses a grid of AND gates and full adders to calculate the partial products of the multiplication, and then sums these partial products to obtain the final product. This method is considered hardware-intensive and expensive, but it is also fast because the calculations are performed in parallel.

- Shift-Add Multiplication: This method is less hardware-intensive than array multiplication. It works by repeatedly shifting the multiplicand and adding it to a running sum, based on the bits of the multiplier. This algorithm applies to both unsigned and positive signed numbers.

- This method requires fewer hardware resources, but it is slower than array multiplication because the calculations are performed sequentially.

- Implementation: Shift-add multiplication can be implemented using a sequential circuit with an adder, accumulator, multiplier, multiplicand registers and control signals. The algorithm involves monitoring the multiplier bits and adding the multiplicand to the partial product accordingly. The process of add and right-shift is repeated for the number of multiplier bits. This process requires n cycles for n times addition.

- Signed Multiplication: To handle signed numbers, the multiplicand and multiplier are converted to positive numbers and multiplied using the shift-add method. The sign of the product is then computed based on the XOR of the signs of the original multiplicand and multiplier. Alternatively, sign extension can be performed on shifts in the shift-add method.

- Booth Algorithm: The Booth algorithm is a more efficient way to handle signed multiplication. It reduces the number of additions required when the multiplier has a sequence of 1’s by recoding the multiplier into a series of 0s and -1s. This method treats both positive and negative two’s complement n-bit operands uniformly.

- Implementation: The Booth algorithm uses a table to determine the operation to be performed based on the current and previous bits of the multiplier (Q). These operations include:

- 00: Shift right with sign extension

- 01: Add M to A, right shift

- 10: Subtract M from A, right shift

- 11: No add, right shift with sign extension

- Implementation: The Booth algorithm uses a table to determine the operation to be performed based on the current and previous bits of the multiplier (Q). These operations include:

- Booth Algorithm: The Booth algorithm is a more efficient way to handle signed multiplication. It reduces the number of additions required when the multiplier has a sequence of 1’s by recoding the multiplier into a series of 0s and -1s. This method treats both positive and negative two’s complement n-bit operands uniformly.

Division

- Restoring Division: This method performs a subtraction of the divisor from the dividend and sets the quotient bit to 1 if the remainder is zero or positive. If the remainder is negative, the dividend is restored by adding back the divisor, and the quotient bit is set to 0. The process is repeated until all the digits in the dividend are considered.

- Non-Restoring Division: This method avoids the restoration step required in restoring division. If the accumulator (A) is positive, it is left-shifted and the divisor (M) is subtracted. If A is negative, it is restored by adding M, then left-shifted, and M is subtracted. This method requires fewer add/subtract operations than the restoring division.

Both restoring and non-restoring division algorithms apply to unsigned and positive signed numbers. For signed numbers, the numbers are converted to positive and the sign is adjusted later. The sign of the result is the XOR of the signs of the divisor and dividend.

Hardware Requirements for Shift-Add Multiplication

Shift-add multiplication is a less hardware-intensive method of multiplication compared to array multiplication. The sources provide a breakdown of the essential hardware components necessary for implementing shift-add multiplication:

- Accumulator Register (A): This register stores the partial product and eventually the final product. It needs to be large enough to hold the potential 2n-bit result of multiplying two n-bit numbers.

- Multiplier Register (Q): This register holds the multiplier. The algorithm iterates through each bit of the multiplier to determine whether to add the multiplicand to the accumulator.

- Multiplicand Register (M): This register stores the multiplicand, which is potentially added to the accumulator in each step based on the multiplier bit.

- N-bit Adder: This is a fundamental component used to add the multiplicand to the accumulator in each step if required by the multiplier bit. The adder needs to be n-bits wide to handle the addition of the n-bit multiplicand to the partial product in the accumulator.

- Control Signals for Shift and Add: These signals control the sequential process of the multiplication, dictating when to shift the registers and when to add the multiplicand to the accumulator. The control signals orchestrate the interaction between the registers and the adder.

Example Implementation:

Consider the multiplication of 13 (1101) and 11 (1011), as illustrated in the sources. The steps involved, along with the associated hardware actions, showcase the interplay of the required components:

-

Initialization:

- The accumulator (A) is initialized to 0.

- The multiplier (Q) is loaded with 1011.

- The multiplicand (M) is loaded with 1101.

-

Iteration through Multiplier Bits:

- The control logic examines the least significant bit (LSB) of Q.

- If the LSB is 1, M is added to A using the adder.

- A and Q are right-shifted by one position.

-

Repetition:

- Steps 2 is repeated for each bit of the multiplier.

-

Final Result:

- After processing all bits of Q, the final product (143 in this case) resides in A.

Note:

The provided steps illustrate a simplified overview of the process. Additional details and considerations might be needed for practical implementations, such as handling overflow, sign extension for signed multiplication, and optimized control sequencing.