Pipelining

Transclude of kvs-talk#evolution-2

Metrics

Important

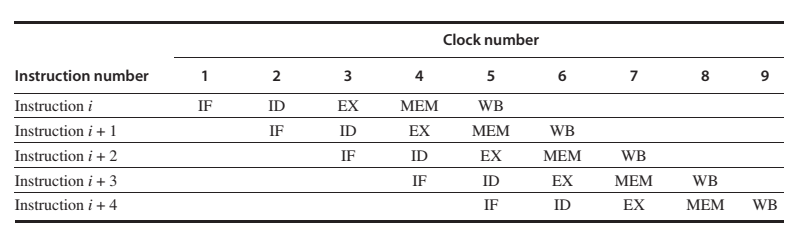

Simple RISC pipeline

On each clock cycle, another instruction is fetched and begins its five-cycle execution.

If an instruction is started every clock cycle, the performance will be up to five times that of a processor that is not pipelined. The names for the stages in the pipeline are the same as those used for the cycles in the unpipelined implementation: IF = instruction fetch, ID = instruction decode, EX = execution, MEM = memory access, and WB = write-back.

Question

Consider the unpipelined processor in the previous section. Assume that it has a 1 ns clock cycle and that it uses 4 cycles for ALU operations and branches and 5 cycles for memory operations. Assume that the relative frequencies of these operations are 40%, 20%, and 40%, respectively. Suppose that due to clock skew and setup, pipelining the processor adds 0.2 ns of overhead to the clock. Ignoring any latency impact, how much speedup in the instruction execution rate will we gain from a pipeline?

Average instruction execution time Clock cycle Average CPI = ×

= 1 ns 40% 20% × [ ] ( ) + × 4 40% 5 + × = 1 ns 4.4 × = 4.4 ns

Hurdles

- Structural: hazards arise from resource conflicts when the hardware cannot support all possible combinations of instructions simultaneously in overlapped execution.

- Data: hazards arise when an instruction depends on the results of a previous instruction in a way that is exposed by the overlapping of instructions in the pipeline.

- Control: hazards arise from the pipelining of branches and other instructions that change the PC.

Hazards in pipelines can make it necessary to stall the pipeline. Avoiding a hazard often requires that some instructions in the pipeline be allowed to proceed while others are delayed. Instructions issued earlier than the stalled instruction—and hence farther along in the pipeline—must continue, since otherwise the hazard will never clear. As a result, no new instructions are fetched during the stall. We will see several examples of how pipeline stalls operate in this section.

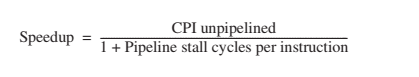

Pipelines with Stalls

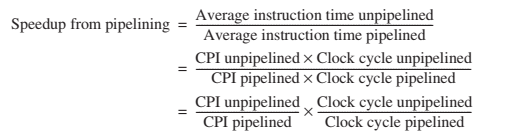

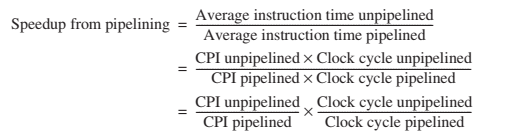

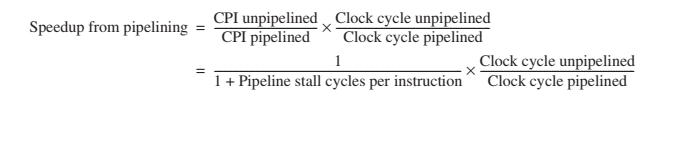

A stall causes the pipeline performance to degrade from the ideal performance. Let’s look at a simple equation for finding the actual speedup from pipelining, starting with the formula from the previous section:

Pipelining can be thought of as decreasing the CPI or the clock cycle time. Since it is traditional to use the CPI to compare pipelines, let’s start with that assumption. The ideal CPI on a pipelined processor is almost always 1. Hence, we can compute the pipelined CPI.

If we ignore the cycle time overhead of pipelining and assume that the stages are perfectly balanced, then the cycle time of the two processors can be equal, leading to:

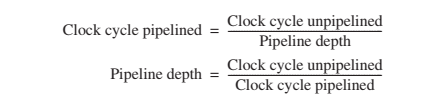

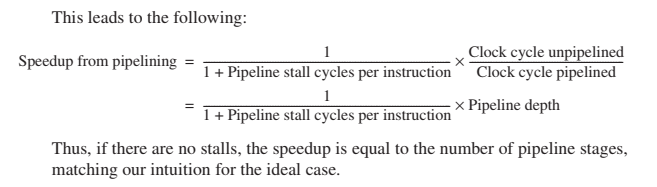

If there are no pipeline stalls, this leads to the intuitive result that pipelining can improve performance by the depth of the pipeline. Alternatively, if we think of pipelining as improving the clock cycle time, then we can assume that the CPI of the unpipelined processor, as well as that of the pipelined processor, is 1. This leads to:

In cases where the pipe stages are perfectly balanced and there is no overhead, the clock cycle on the pipelined processor is smaller than the clock cycle of the unpipelined processor by a factor equal to the pipelined depth:

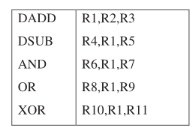

Minimizing Data Hazard Stalls by Forwarding

This be solved with a simple hardware technique called forwarding (also called bypassing and sometimes short-circuiting). The key insight in forwarding is that the result is not really needed by the DSUB until after the DADD actually produces it. If the result can be moved from the pipeline register where the DADD stores it to where the DSUB needs it, then the need for a stall can be avoided. Using this observation, forwarding works as follows:

- The ALU result from both the EX/MEM and MEM/WB pipeline registers is always fed back to the ALU inputs.

- If the forwarding hardware detects that the previous ALU operation has written the register corresponding to a source for the current ALU operation, control logic selects the forwarded result as the ALU input rather than the value read from the register file.

Notice that with forwarding, if the DSUB is stalled, the DADD will be completed and the bypass will not be activated. This relationship is also true for the case of an interrupt between the two instructions.

Data Hazards Requiring Stalls

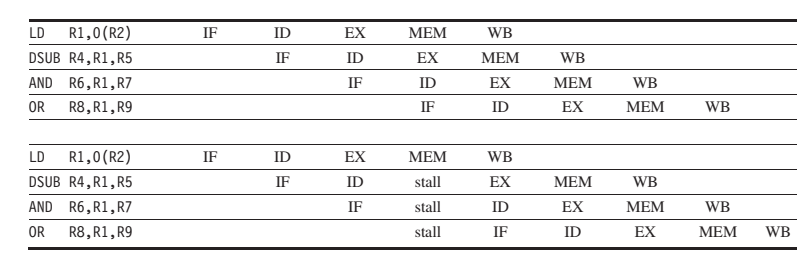

This case is different from the situation with back-to-back ALU operations. The LD instruction does not have the data until the end of clock cycle 4 (its MEM cycle), while the DSUB instruction needs to have the data by the beginning of that clock cycle. Thus, the data hazard from using the result of a load instruction cannot be completely eliminated with simple hardware.

Such a forwarding path would have to operate backward in time—a capability not yet available to computer designers! We can forward the result immediately to the ALU from the pipeline registers for use in the AND operation, which begins 2 clock cycles after the load. Likewise, the OR instruction has no problem, since it receives the value through the register file.

The load instruction has a delay or latency that cannot be eliminated by forwarding alone. Instead, we need to add hardware, called a pipeline interlock, to preserve the correct execution pattern. In general, a pipeline interlock detects a hazard and stalls the pipeline until the hazard is cleared. In this case, the interlock stalls the pipeline, beginning with the instruction that wants to use the data until the source instruction produces it. This pipeline interlock introduces a stall or bubble, just as it did for the structural hazard. The CPI for the stalled instruction increases by the length of the stall (1 clock cycle in this case).

In the top half, we can see why a stall is needed: The MEM cycle of the load produces a value that is needed in the EX cycle of the DSUB, which occurs at the same time. This problem is solved by inserting a stall, as shown in the bottom half.

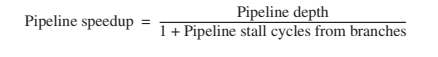

Performance of Branch Schemes

Pipeline stall cycles from branches = Branch frequency × Branch penalty

As pipelines get deeper and the potential penalty of branches increases, using delayed branches and similar schemes becomes insufficient. Instead, we need to turn to more aggressive means for predicting branches. Such schemes fall into two classes: low-cost static schemes that rely on information available at compile time and strategies that predict branches dynamically based on program behavior.